Norridgewock Massacre:

Dreams, Inspirations, Tragedies

Story by Douglas Lepley

Photographs by Julie Bowen

The editors of Mainely Local first became aware of the "Norridgewock painting" during a conversation with artist, Conrad Ray. he told us he was soon going to be completing the small remaining portion of a wall-sized mural that he had begun in 1980. The painting was started for one reason...and finished for another. As we talked to Mr. Ray, we realized that the story went back more than just a few years. It actually goes back to 1724...

"People forget important anniversaries," muses Waterville resident and local historian Arthur Grenier. "August 23, 1974 was the 250th anniversary of the Norridgewock Massacre, and the suffering and inspiration of that event had been forgotten."

But Arthur remembered...he remembered a devout French Jesuit priest named Sebastian Rasle who had dedicated his life to serving the Norridgewock Indians at Old Point, Maine, near present day Madison. he remembered a bloody August afternoon in 1724 that ended Father Rasle's life and drove the Norridgewocks from their home. Arthur Grenier remembered, and began what was to become a ten-year endeavor to preserve the memory of Father Rasle and the Norridgewocks. His dream of making history live led him to the excavation and collection of Norridgewock relics, to the construction of two museums, and to the founding of a parade and festival still held each August in Madison.

Arthur's enthusiasm also proved inspirational. in 1980, another man met Arthur, soon shared his dream of preserving history, and created his own remembrance of the heroism and tragedy of Norridgewock.

To see this remembrance, enter the bottle redemption center (one of Arthur's former museums) in Oosoola Park in Norridgewock and head for the back wall. Lift aside cases of empty Michelob bottles and large clear plastic bags of Pepsi cans, and behold a marvelous wall-sized mural of the Norridgewock Massacre. This detailed painting, based on carefully researched fact and vividly depicting the human emotion of attack and dream shattered, is the work of Waterville artist Conrad Ray, another man dedicated to keeping alive important anniversaries. Indeed, the story of all three men - Rasle, Grenier, and Ray - is an inspiring tale of human struggle to make dreams live.

On August 19, 1724 an expedition of 208 English militiamen accompanied by three Mohawk Indians left Fort Richmond, Maine, in seventeen whaleboats and began a journey up the Kennebec River. The purpose of this mission was to rout the Indians at Norridgewock and capture the Jesuit priest named Rasle, whom the English believed was leading the Norridgewocks on raids of English settlements.

This was to be one more struggle in a series of conflicts that we refer to broadly as the French and Indian Wars.

On the twenty-first of August the expedition landed at Ticonic Falls at Winslow, Maine. There they left their boats with a force of forty men to guard them and began a cross country march toward Old Point, the site of the Norridgewock village. Although this would be the fourth raid on the Norridgewocks (Father Rasle had barely escaped with his life during a previous raid), the English were not quite sure of the village's location.

Then, a few miles from Old Point, they happened upon the Abenaki Chief Bomazeen with his wife and daughter. The family tried to flee, but Bomazeen and his daughter were shot and killed, and the wife was taken captive. The English tortured the wife into leading them to the village.

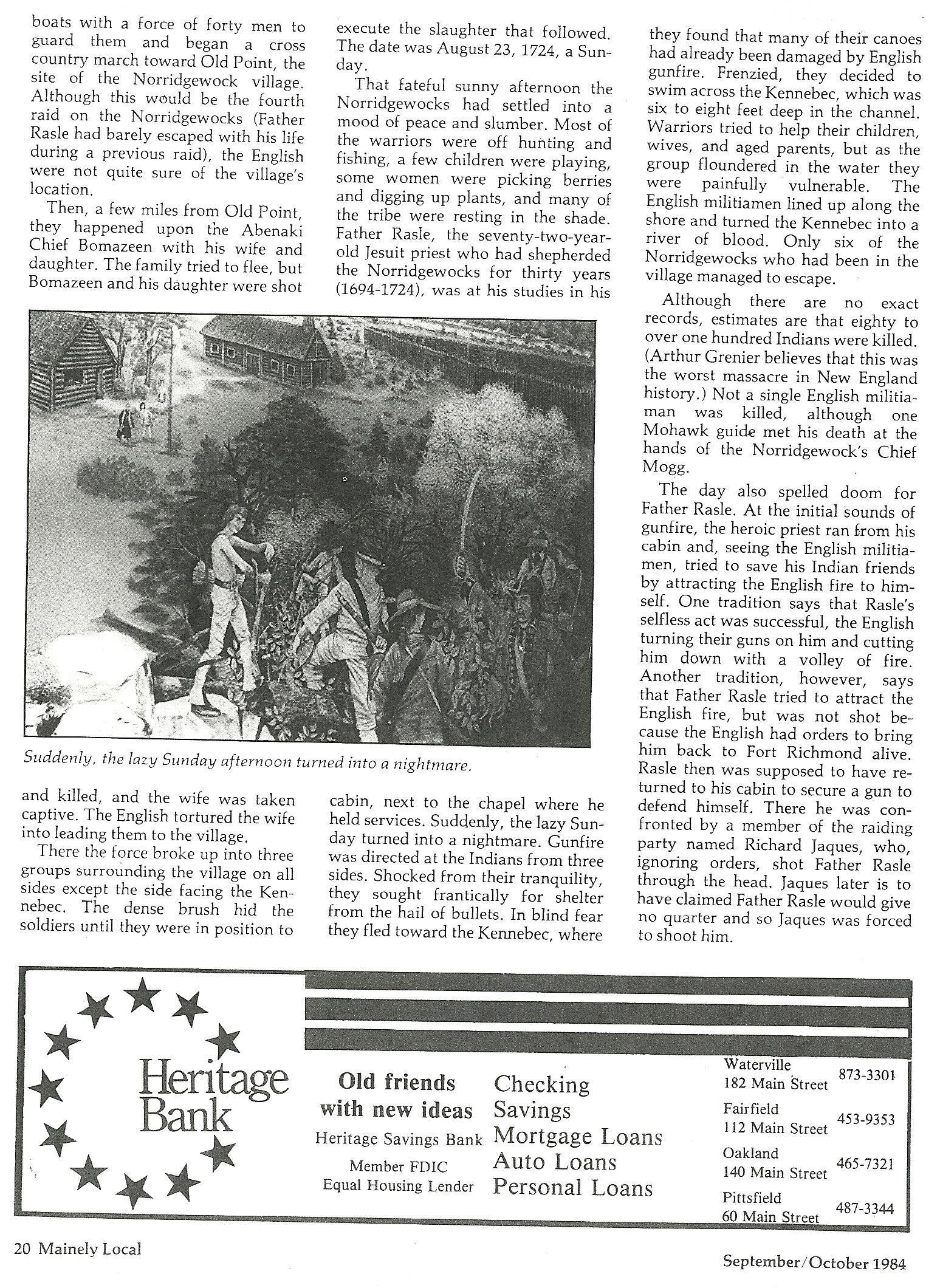

There the force broke up into three groups surrounding the village on all sides except the side facing the Kennebec. The dense brush hid the soldiers until they were in position to execute the slaughter that followed. The date was August 23, 1724, a Sunday.

That fateful sunny afternoon the Norridgewocks had settled into a mood of peace and slumber. Most of the warriors were off hunting and fishing, a few children were playing, some women were picking berries and digging up plants, and many of the tribe were resting in the shade. Father Rasle, the seventy-two-year-old Jesuit priest who had shepherded the Norridgewocks for thirty years (1694-1724), was at his studies in his cabin, next to the chapel where he held services. Suddenly, the lazy Sunday turned into a nightmare. Gunfire was directed at the Indians from three sides. Shocked from their tranquility, they sought frantically for shelter from the hail of bullets. In blind fear they fled toward the Kennebec, where they found that many of their canoes had already been damaged by English gunfire. Frenzied, they decided to swim across the Kennebec, which was six to eight feet deep in the channel. Warriors tried to help their children, wives, and aged parents, but as the group floundered in the water they were painfully vulnerable. The English militiamen lined up along the shore and turned the Kennebec into a river of blood. Only six of the Norridgewocks who had been in the village managed to escape.

Although there are no exact records, estimates are that eighty to over one hundred Indians were killed. (Arthur Grenier believes that this was the worst massacre in New England history.) Not a single English militiaman was killed, although one Mohawk guide met his death at the hands of the Norridgewock's Chief Mogg.

The day also spelled doom for Father Rasle. At the initial sounds of gunfire, the heroic priest ran from his cabin and, seeing the English militiamen, tried to save his Indian friends by attracting the English fire to himself. One tradition says that Rasle's selfless act was successful, the English turning their guns on him and cutting him down with a volley of fire. Another tradition, however, says that Father Rasle tried to attract the English fire, but was not shot because the English had orders to bring him back to Fort Richmond alive. Rasle then was supposed to have returned to his cabin to secure a gun to defend himself. There he was confronted by a member of the raiding party named Richard Jacques, who, ignoring orders, shot Fatehr Rasle through the head. Jacques later is to have claimed Father Rasle would give no quarter and so Jacques was forced to shoot him.

After the battle ended, the English scalped Father Rasle, pulled out his eyes, filling the sockets and his mouth with mud, crushed his skull with tomahawks, and broke all of his limbs. Father Rasle's scalp was later taken to Boston, where a one hundred pound reward was being offered for his capture or death. The militiamen spent the night at Old Point. The next morning as they left, they burned Father Rasle's cabin and chapel.

After the raiding party departed, the survivors of the attack and the warriors who had been hunting and fishing returned to their village. They found the body of their beloved priest and buried him with reverence and honor. Among the ashes they also found the chapel bell. This they buried at the base of a tree near Father Rasle's grave. Years later, when the tree fell over, the bell was revealed and recognized as Rasle's bell. it was preserved and today can be seen among the Maine Historical Society's collection in Portland, Maine. After burying Rasle, the Norridgewocks fled north to join other members of the Abenaki tribe - their power in the Old Point area broken forever.

Despite the English perception of Rasle as a treacherous renegade who led attacks on defenseless settlers, he was really a man of quite another mettle. A member of an illustrious French family, Rasle was a gentleman by birth and an outstanding classical scholar. He had before him a life of relative ease, but, inspired by the sacrifices of other Jesuit missionaries to America, he decided to give up his material comforts and family ties in France to help the Indians.

He arrived in America in 1689 and in Norridgewock in 1694. Among the Indians he was considered friend, benefactor, and spiritual guide. He spoke the Indians' language, joined them on hunting and fishing trips, worked beside them in their fields, and helped with such tasks as making maple sugar and candles. He nursed them when they were sick and helped settle quarrels at their council meetings. He was anxious over their daily struggle for food. In a letter he writes:

“Here I am, in a cabin in the woods, in which I find both crosses and religious observances among the Indians. At the dawn of the morning I say Mass in the chapel, made of the branches of the fir-tree, the residue of the day I spend in visiting and consoling the savages. It is a severe affliction to see so many famished persons without being able to relieve them.”

When the Indians went hungry, Father Rasle went hungry, too.

Father Rasle also helped to defend the Indians' lands and rights against the encroachments of the English. He often accompanied the Norridgewocks to peace treaty talks to warn them against English violations of prior treaties and agreements.

But most of all, Father Rasle was the Norridgewocks' spiritual guide. He catechized the young and preached to the old. As he reports in a letter to his nephew:

“They have built two chapels at about three paces from the village...Since they are both on the road which leads either to the woods or into the open country, the savages never pass without offering their prayer.”

Rasle built a portable altar so that when the Indians went on long journeys, they might continue their worship of God. He also began a "choir" of forty young Indians.

Because of Rasle's devotion to the Indians, they loved him. Having suffered a bad leg fracture that never properly healed, Rasle was incapable of walking long distances. The Indians, therefore, made a little to carry Rasle with them on their long trips so they could enjoy his friendship and counsel.

While a compassionate man, Rasle was also resolute and courageous. When his first chapel at Norridgewock was burned down in 1705 by an English raiding party (Rasle was not at home), he returned and began his mission again. Having barely escaped a 1722 raid with his life, he returned to continue his work. Warned by church leaders in Quebec that the English were making a determined effort to capture or kill him, he remained. He had come to help the Norridgewocks, and no threat could cause him to leave. He perhaps best sums up his dream in the following passage from one of his letters:

“They came in crowds to make me share their pains and unquietudes or to communicate to me subjects of complaint against their countrymen, or to consult me about their marriages and other particular affairs. It is necessary for me to instruct some, to console others, to reestablish peace in families at variance, to calm troubled consciences, to corrects others by reproofs mingled with gentleness and charity, in short, as much as it is possible, to render them all contented.”

Such was the man the English killed and mutilated; his dream of physical and spiritual contentment for the Norridgewocks is what they destroyed.

In 1833, Bishop Fenwick of Boston decided to honor Father Rasle. In August of that year a monument was erected at Old Point on the site where Father Rasle's cabin and chapel had stood. Three thousand people attended the impressive ceremony, and Indians sang in the choir just as Indians had sung in Father Rasle's choir. The text of the dedication address would have pleased Arthur Grenier because it emphasized the permanence of Father Rasle's reputation:

“The memory of him shall not depart away, and his name shall be in request from generation to generation. Nations shall declare his wisdom and the church shall show forth his praise.”

In 1836 the monument was vandalized, but it was reerected on a new base and stands today at the back of the cemetery at Old Point.

A number of relics have survived the various English raids and the ravages of time. In addition to the chapel bell, Father Rasle's strongbox, a book of inspiration readings, and an iron cross Father Rasle wore around his neck can be found at the Maine Historical Society building in Portland. According to oral tradition, the iron cross that stood atop Father Rasle's chapel was transported to Old Town and can be seen at St. Ann's Church on Indian Island. One of Father Rasle's greatest accomplishments was the compilation of a dictionary of the Abenaki Indian language. This dictionary was captured by Colonel Westbrook during his 1722 raid of Norridgewock and is preserved today at Harvard University's Houghton Library.

It was Father Rasle, the devout priest and dedicated friend of the Indians, who enchanted Arthur Grenier. In 1974 on the 250th anniversary of the Massacre, Grenier decided to keep the memories alive. He founded a celebration in Madison to commemorate the Norridgewock Massacre: "I was a committee of one. I organized the biggest parade Madison ever had, and today every year they have the Norridgewock Days." In addition to the parade, Madison also held a corn festival, and citizens, dressed as militiamen, demonstrated colonial fighting tactics. This parade and festival are still held in Madison each year on the weekend nearest August 23. A Mass and dancing have been added to the celebration.

In 1974, Grenier also began his first museum dedicated to the period of the Norridgewock Massacre. The building was erected across the road from the monument at Old Point. It contained life-sized dioramas depicting Indian life and customs. The building also housed some excavated relics from the area. But being in such an isolated location, the museum was a favorite target for vandals, who damaged the display and stole relics. Then in 1979 a storm damaged the building at a time when Arthur was in the hospital. This was the final straw and Arthur decided to sell the museum, which today is the site of Elias Monuments.